HIV research by Fogarty trainees brings changes to US treatment protocols

May / June 2017 | Volume 16, Issue 3

Photo by Richard Lord for Fogarty

Expertise developed through Fogarty's research training

programs helped to make a landmark multi-site

international HIV study possible.

By Karin Zeitvogel

When the astounding results of a multi-site international HIV/AIDS study were published in 2011, they had an immediate impact, causing the U.S. and governments around the world to change their treatment protocols, saving countless lives. The research project, known as HPTN 052, demonstrated that providing antiretroviral treatment as soon as an individual is diagnosed with HIV cuts the risk of the virus being transmitted to an uninfected partner by more than 90 percent.

It wouldn't have been possible without the expertise developed through Fogarty's research training programs, said one of the trial's principal investigators.

"Long before we launched the pilot study in 2005, Fogarty was offering training in resource-constrained countries where there were few or no doctors, nurses and clinics, and certainly no research capacity," said Dr. Myron Cohen who, in addition to helping lead the HIV Prevention Trials Network (HPTN), is a professor of medicine at the University of North Carolina (UNC), Chapel Hill.

"All of the nine countries that we worked in for HPTN 052 had investigators who had Fogarty support during their training. In other words, we were only able to consider running the trial because Fogarty had worked so hard to get people ready for it," Cohen said.

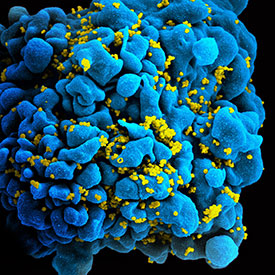

Image courtesy of NIAID

Fogarty trainees and research

partners discovered immediate

treatment for those diagnosed

with HIV can dramatically reduce

risk of transmission.

HPTN 052, which was funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), was the first randomized clinical trial to show that providing an HIV-infected individual with antiretroviral therapy (ART) when their immune system was still relatively healthy dramatically reduces the risk of sexual transmission of HIV to an uninfected partner.

Many of the local investigators in the nine countries where the study was conducted - Botswana, Brazil, India, Kenya, Malawi, South Africa, Thailand, Zimbabwe and the U.S. - were trained through Fogarty's AIDS International Training and Research Program (AITRP) or its International Implementation, Clinical, Operational and Health Services Research Training Award for AIDS and Tuberculosis (IICOHRTA-AIDS/TB). Both programs prepared personnel to be shovel-ready to conduct research on key global health issues, such as HIV.

Other investigators, like Dr. James Hakim, a professor of medicine at the University of Zimbabwe College of Health Sciences, or Dr. Suwat Chariyalertsak, head of the AIDS Prevention and Microbicide Clinical Research Site at Chiang Mai University in northern Thailand, completed higher degrees with Fogarty support and are now principal investigators with their own Fogarty grants. Still others took part in short-term training programs supported by Fogarty.

Fogarty helps build research expertise

Such support from Fogarty was essential to the success of the HPTN trial, said Dr. David Celentano of Johns Hopkins University. "When I first arrived in northern Thailand in 1991," Celentano said, "there was an eager, but pretty much untrained group."

After receiving a Fogarty award a few years later, Celentano said Johns Hopkins brought several people from Chiang Mai University to the U.S. for advanced degree studies and 50-60 people for an intensive, three-week summer institute for epidemiology and biostatistics, Celentano said. "We trained many of the epidemiologists that have been very active in the HIV epidemic in northern Thailand. There are a lot of really well-trained people in Chiang Mai now, which wouldn't have happened without Fogarty."

Similarly, when Dr. Mina Hosseinipour, a professor of medicine at UNC Chapel Hill, moved to Malawi in 2001, she found no local scientists trained in internal medicine or infectious diseases, no one with the research experience required to run a study like HPTN 052, and no one with expertise in infectious disease or HIV management.

"But Malawi did have a Fogarty AITRP since 1998, and many faculty members at the College of Medicine were former or current Fogarty grantees," Hosseinipour said. The first local health care professional who was hired to work on HPTN 052 in Lilongwe in the early 2000s, Dr. Cecilia Kanyama, was not only a Fogarty alumna but also a graduate of the Malawi College of Medicine. "Today, we have in Malawi a wealth of incredibly well-trained people who know how to do research, know how to lead agendas. And they're all products of Fogarty training - all of them," said Hosseinipour, who is now the scientific director of UNC-Project Malawi.

At the annual meeting of the HPTN group, held in Washington, D.C. in April 2017, NIAID Director Dr. Anthony S. Fauci, praised Fogarty's "extraordinary track record in training the future leaders in global health throughout the world."

"Many of the health leaders in the developing world have had their core research and global health training through the Fogarty International Center," Fauci said. "Fogarty is a critical component of the NIH's global health research agenda."

Training people in developing countries benefits the U.S.

Training people in low- and middle-income countries like Malawi or Thailand to conduct research is in the best interest of the U.S., HPTN investigators said. Not only is the world more interconnected today - "A lot of Americans go to Thailand and elsewhere, and they can encounter a whole lot of infectious diseases in their travels," said Celentano - but conducting HPTN 052 in developing countries with a higher incidence of HIV infection than the U.S. gave investigators a broader pool of infected people to study, and produced results more quickly. Because of the geographic spread and diversity of the participants, the study was also easy to generalize to people not from the nine countries studied.

"If HPTN 052 had been run in the U.S. only, it would still be going on," said Hosseinipour. Instead, initial results became available in mid-2011, after a median follow-up of just a year and eight months.

Photo courtesy of NIAID

The study’s final results showed a 93 percent

reduction of HIV transmission when antiretroviral

therapy was given immediately to infected people.

Within weeks of the interim results being made public, all U.S. organizations that provided HIV care had "amended their guidelines to provide immediate antiretroviral treatment to anyone diagnosed with the virus," Cohen said. By 2012, countries around the world had followed suit and were providing ART to HIV-infected patients as soon as the virus was detected. Prior to the results of HPTN 052, the WHO recommended that ART be given only when the CD4 lymphocyte count of an infected person fell below a certain level, indicating that HIV had progressed. HPTN 052 showed there were benefits to both members of a couple in providing ART when the immune system was still relatively healthy.

Nearly 90 percent of study participants stayed with HPTN 052 until the study ended in May 2015. After the final results were published - showing a 93 percent reduction of HIV transmission when ART was given immediately to infected people.

"Treatment as prevention became the centerpiece of stopping the transmission of HIV, both in the U.S. and worldwide," said Cohen. "Because Fogarty developed research sites all over the world, because Fogarty trained all those people worldwide, countless lives have been saved, including in the U.S."

More Information

To view Adobe PDF files,

download current, free accessible plug-ins from Adobe's website.