Because of a lapse in government funding, the information on this website may not be up to date, transactions submitted via the website may not be processed, and the agency may not be able to respond to inquiries until appropriations are enacted. The NIH Clinical Center (the research hospital of NIH) is open. For more details about its operating status, please visit

cc.nih.gov. Updates regarding government operating status and resumption of normal operations can be found at

opm.gov.

Modeling networks: How Fogarty made epidemiology history during the COVID-19 pandemic

May / June 2021 | Volume 20 Number 3

By Susan Scutti

Relationship-building and a commitment to open science underpinned Fogarty’s many modeling triumphs during the COVID-19 pandemic. “Our international work has always been quite opportunistic,” said Dr. Cécile Viboud, senior staff scientist. In 18 years with Fogarty’s

Division of International Epidemiology and Population Studies, Viboud has worked with pretty much any scientist wishing to collaborate on modeling projects and respiratory virus surveillance. “We had this network of collaborators that we had built for a long time and that helped Fogarty to begin sharing COVID-19 information early on,” she said. In particular, collaborations with one team of Chinese scientists have been “incredibly productive.” Dr. Hongjie Yu, originally part of the Chinese CDC, had spent time at the U.S. CDC and the NIH several years ago. “He has since gone back to China and is now at Fudan University, where he has been a great resource,” said Viboud. “He also has a lot of good ideas.”

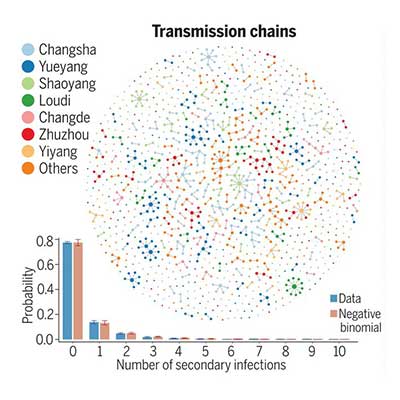

Courtesy of Sun et al. 2021.Fig. 1 SARS-CoV-2 transmission chains.Fogarty’s disease modeling team studied transmission chains among SARS-CoV-2-infected individuals in China’s Hunan province.

Courtesy of Sun et al. 2021.Fig. 1 SARS-CoV-2 transmission chains.Fogarty’s disease modeling team studied transmission chains among SARS-CoV-2-infected individuals in China’s Hunan province.

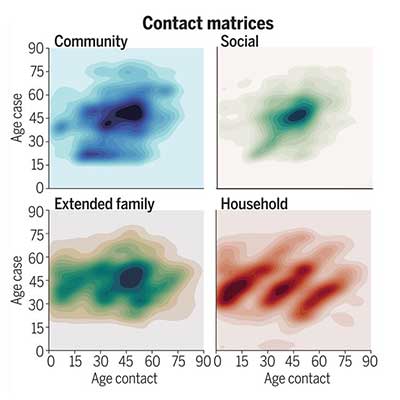

Courtesy of Sun et al. 2021.Fig. 2 Heterogeneity in contact rates of SARS-CoV-2 cases and impact of interventions, separated by contact type.

Courtesy of Sun et al. 2021.Fig. 2 Heterogeneity in contact rates of SARS-CoV-2 cases and impact of interventions, separated by contact type.

Also playing an instrumental role was Fogarty’s Chinese postdoctoral fellow, Dr. Kaiyuan Sun, who happened to be visiting family in China when the outbreak began. Soon back in the U.S., he saw the Chinese authorities were providing open-source data on early cases, including age, sex, travel and exposure history, and disease severity. “This was a big deal,” Sun said. He and the team quickly collected, translated and formatted the information and shared it online. “We were the first group to share this type of data and after us other groups began to do the same.”

For Sun, research is all about relationships and connections. For example, his former collaborator, Dr. Marco Ajelli at Indiana University, noticed Sun’s data sharing efforts online. Through Ajelli, the Fogarty team established a relationship with Fudan University and the Hunan CDC. That resulted in an

important

Science publication that estimated half of all transmissions occurred before patients showed symptoms, a unique feature of the SARS-CoV-2 virus and disease. Another significant contribution came from scientists in the Netherlands who used the data compiled by Sun to estimate the virus’s incubation period, instrumental in establishing quarantine guidelines.

Deciding which pandemic-related project has been most important is difficult, said Viboud. “Our six-month projections via the Scenario Modeling Hub have been our most policy-relevant work; we’ve sent them to the White House, the CDC, the WHO and also some state governors.” The CDC invited the scientists to publish an MMWR report on May 5th to help formulate guidance for local jurisdictions. When CDC Director Dr. Rochelle Walensky discussed the data at a White House press briefing, Viboud said the team realized that their projections were actually being used. A

paper that appeared in

JAMA Internal Medicine last summer is another undeniable standout. “This is the most read paper published in the journal ever. Not only was it the first estimation of excess mortality, but it also described conditions in New York City and the eastern seaboard, and drew comparisons to the 1918 flu pandemic,” said Viboud.

Another significant paper looked at the early dynamics of the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic in Portugal and featured Fogarty’s Dr. Nídia Trovão as co-lead-author. Trovão’s pandemic work also included training scientists in low-and middle-income countries (LMICs) to use a portable genomic sequencing platform to generate full SARS-CoV-2 genomes, create genomic databases, and study virus mutation patterns and evolutionary dynamics. The immediate goal was to produce SARS-CoV-2 sequences to aid in pandemic response. Longer term, the hope is that genomics will help LMIC scientists better understand the viral dynamics within their countries so they can implement public health strategies to control them. “They are no longer dependent on scientists in higher-income countries to identify, analyze and interpret their results,” Trovão observed.

“Despite the pandemic, we were able to run virtual workshops and train many scientists from Africa and Asia on topics from sample processing to complex analyses; this will pave the way for improved surveillance of COVID-19 variants globally and mitigate future pandemics” said Dr. David Spiro, division director.

Currently, Fogarty’s modelers are looking at the whole period and trying to tease out the overall impact of SARS-CoV-2, said Viboud. “For example, were people anxious and losing hope, committing suicide, using opioids? Were people turning away from the medical system at the height of the pandemic and then dying from that? We’re trying to understand the direct and indirect impacts.”

More Information

- Fogarty

Division of International Epidemiology and Population Studies

-

Estimation of excess deaths associated with the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States, March to May 2020, co-authored by Fogarty's Dr Cecile Viboud

JAMA Internal Medicine, July 1, 2020 -

Transmission heterogeneities, kinetics, and controllability of SARS-CoV-2, featuring Fogarty's Dr Kaiyuan Sun as lead author, and Fogarty's Dr Cecile Viboud as co-senior author

Science, November 24, 2020 -

The early dynamics of the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic in Portugal [Preprint], co-authored by Fogarty's Dr Nídia S Trovão

medRxiv, February 23, 2021

To view Adobe PDF files,

download current, free accessible plug-ins from Adobe's website.