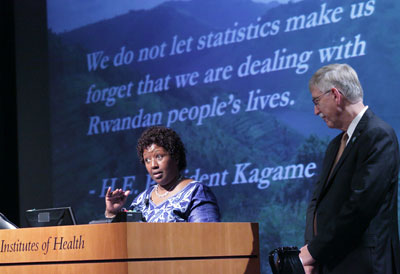

Rwandan Minister of Health Dr Agnes Binagwaho discusses country's health advances

September / October 2015 | Volume 14, Issue 5

Photo by Bill Branson/NIH

Rwandan Minister of Health, Dr. Agnes Binagwaho, told an NIH audience

how her country has used evidence to improve health outcomes.

Rwandan Minister of Health, Dr. Agnes Binagwaho, recently visited the NIH and shared the lessons learned during her country's dramatic recovery from the 1994 genocide. She said health has improved significantly, largely because of policy decisions based on scientific evidence, and such information should flow more freely so low-income countries can access it.

Noting that some people wanted to write off Rwanda after the genocide, the Minister described how her country emerged from the ruins a healthier nation. During the past two decades, life expectancy has more than doubled and child mortality has dropped by two-thirds. The vast majority of Rwandans - about 90 percent - have health insurance. Most children receive the recommended vaccines. The percentage of girls vaccinated against the human papillomavirus to prevent cervical cancer is higher in Rwanda than in the U.S. and so, too, is the percentage of HIV-positive people on antiretroviral treatment for prevention.

Binagwaho delivered the 2015 David E. Barmes Global Health Lecture, which honors Dr. Barmes, a dentist and epidemiologist who devoted his career to conducting research to improve health in developing countries. The Minister's talk, "Medical Research and Capacity Building for Development: The Experience of Rwanda," touched on equity, ethics and evidence.

In rebuilding after genocide, she said the government created a health system that reaches out to the poor and vulnerable because "when we have them in the loop, we have everybody." Health programs are implemented or revised based on evidence of impact on the community.

"It's not about the money, it's about the system," she said. Rwanda's leaders use research "to see all the possibilities," so they can best invest their health care funds. "We have achieved more with less money than the majority of other countries."

Photo by Bill Branson/NIH

Dr. Agnes Binagwaho, Rwanda's Minister of Health,

delivered the 2015 David E. Barmes Global Health lecture,

which is sponsored by Fogarty and the National Institute

of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR). From left:

Fogarty Director Dr. Roger I. Glass, NIDCR Director Dr. Martha

J. Somerman, NIH Director Dr. Francis S. Collins,

Dr. Binagwaho and Rwanda's Ambassador to the U.S.,

Mathilde Mukantabana.

By investing in its people, Rwanda improved its economy. "Better health turns into better wealth," she noted, pointing to statistics showing that as life expectancy doubled, the per capita GDP more than quadrupled. "A healthy workforce means economic growth. A better health system means a healthy workforce."

Moving forward, she said, Rwanda needs to write its own history and empower its own experts. To grow its research capacity, the government requires that all research conducted in the country include Rwandan principal investigators and papers on the findings must be written jointly with Rwandan authors. Research has to be "win-win" for all stakeholders, she said.

To improve services to the people, the leaders of Rwanda's government programs are being educated in implementation science, the science of service delivery. Four members of her ministry, recently trained at Harvard University, and are now returning to Rwanda to help train others at the newly created University of Global Health Equity. "By taking stars in program management and turning them into researchers and academicians," she said, they can now "teach other people in Africa and elsewhere how to do business in another way." The training initiative is designed so students can stay on the job while gaining skills and knowledge relevant to their work responsibilities.

"As a scientific community, we have a moral responsibility to the world," Binagwaho told the audience. Research should be done with the consumer in mind and benefit the people being studied, she added. Discoveries detailed in peer-reviewed articles should be openly available for people in low-income countries. "If you have to pay half your salary to get information, you can't get information," she said, noting that she makes sure to publish only in open-source outlets. "It's important to make information available to low-income countries for scientists and implementers, so we can produce quality service to the people and improve the way we do research."

Capacity building is the most important factor in making a health system resilient, she observed, and research should be done in a participatory manner. "We have so much to tell the world, and so much to learn from the world that we need to create that partnership," she urged. "We can't let global health research momentum decrease."

More Information

To view Adobe PDF files,

download current, free accessible plug-ins from Adobe's website.