Africa transforms its medical education with Medical Education Partnership Initiative (MEPI) - Page 2

September / October 2012 | Volume 11, Issue 5

(Page 2 of 2)

Page 1 | Page 2

Focusing on faculty

All Medical Education Partnership Initiative (MEPI) institutions are moving to counter the brain drain of faculty and medical personnel that has plagued African health sectors. A key approach is to build a quality research infrastructure at medical schools and allow faculty protected research time. This can keep staff engaged, nurture professional growth and help tether them to their positions.

MEPI partners also recognize the synergy between research, education and patient care, with robust activity in each aspect improving the quality of the whole. By enabling faculty to conduct research, medical schools not only provide career paths for investigators, but also generate discoveries about local health problems that inform health authorities in the country and across the region. "This is a critical aspect of the effort," said Dr. Myat Htoo Razak, who oversees Fogarty's engagement in MEPI. "Locally relevant research is essential for evidence-based health services and policy decisions."

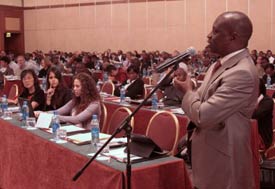

Photo by Richard Lord for Fogarty/NIH

Dr. Nelson Sewankambo (on right), who runs

Uganda's MEPI project and leads a council of his

peers, teaches up-to-date curricula to a growing

number of Ugandan medical students.

With MEPI funds, the University of Nairobi developed three research-oriented programs, including a year-long, mentored fellowship in implementation science, a career development award in clinical research and a dozen small faculty research grants. It also offers grant proposal writing classes to help broaden dissemination of research findings.

"We want to increase the number of theses that people write that get published in peer-reviewed journals," said Dr. James Kiarie, project leader at Kenya's University of Nairobi. "Currently it is less than 1 percent. We want to increase that to 50 to 60 percent. We initially felt not so many people would be interested, but the response has been overwhelming .... We suddenly have people who believe in research, are asking for help in writing grants."

In Mozambique, the Universidade Eduardo Mondlane is using MEPI funds and advice from partners at the University of California, San Diego to establish an infrastructure for research. It's building laboratories and offering courses in methodology, grant proposal and paper writing. "If physicians are able to write research grants and get funded, they will feel professionally happy and will be able to improve conditions in the work place. They get incentives to improve their salaries and increase their knowledge," said project leader Dr. Emilia Noormahomed.

In Nigeria, the University of Ibadan is making some funding available to postgraduate students, resident doctors and junior faculty as a way to spark interest in research careers. Funded projects include local health studies on the hepatitis E virus in pigs and humans, and HIV's impact on infant hearing.

Another tack to encourage retention is to support faculty for time off to update their training, holding their jobs open and even offering promotions on their return.

In an uncommon approach, the University of Zambia paired 18 faculty members with others in similar or complementary areas of academic focus, so they can learn from and support each other in their work and become more anchored in their positions.

Establishing rural training sites

Photo by Richard Lord for Fogarty/NIH

Africa’s remote areas have limited medical service.

MEPI funds are contributing to new rural training

programs to attract local students, who would be

more likely to remain in the area once qualified.

Most of Africa's population lives in rural areas, yet health care workers are located overwhelmingly in urban centers. Persuading staff to move far from the cities, to live and work in relative isolation, has long been a challenge. To fix this, universities are taking a number of steps. They're building rural residency requirements into medical curricula, collaborating with government officials to improve rural staffing levels, technology and living conditions, and are developing remote training centers for local students, who're more likely to remain in their home communities once qualified.

Faculty in South Africa are collaborating with the national health department to develop training sites in five villages as part of a rural teaching network. The sites will incorporate an electronic repository of learning materials, video conference links, Internet access and other distance learning aids. Medical students training in urban centers must perform community service by identifying a disadvantaged population, such as orphans or the homeless, and choosing an activity to improve their condition.

Some populations are so remote that the students and faculty need to reach them by small plane to bring them medical attention. "It is an innovative way to use modern technology to take the medical schools to the rural areas and to make these areas attractive to trainees," said Dr. Umesh Lalloo, project leader at UKZN.

Uganda made a bold move to embrace far-flung areas in its training plans, priming 95 new rural sites to offer standardized curricula. Meanwhile, Kenya is networking nine district hospitals to offer quality instruction in their communities.

In some countries, community health services are being built from a basic level. In Zambia, grantees bought a bus and will subsidize fuel to allow students and faculty to travel to some hard-to-reach areas.

Boosting connectivity and e-learning

Broader use of electronic resources is essential to curriculum reform and quality training, especially in rural settings. The Internet provides extensive e-learning resources and keeps students up-to-date. Some sub-Saharan countries are using MEPI funds to improve power supplies and wiring for Internet connections. In other places, the focus is on upgrading hard- and software and building e-libraries.

Photo by Richard Lord for Fogarty/NIH

Electronic resources are integral to modern medical

training. MEPI funds are enhancing power supplies,

wiring and equipment to improve Internet access.

At the University of Nairobi, the medical school solicits curriculum ideas from its students, who are often adept at assessing new technology and electronic resources. The institution supports student-led seminars, focus groups, journal clubs and workshops.

With MEPI resources, the university's medical library now has 50 new computers offering electronic teaching tools, guidelines on care and treatment, and access to scientific journals. To keep students and faculty in rural areas abreast of the latest information, MEPI funds were used to purchase 50 new smartphones, which have been loaded with guidelines on topics such as diarrhea treatments for children and nutritional needs of HIV-positive children. Health care workers who can immediately consult guidelines have been shown to follow them more closely.

Sharing best practices

While MEPI directly supports some 30 individual institutions, project leaders are sharing the fruits of the program with their rural training outposts, other medical schools in the network and beyond, to build synergies and together lift the region's health sector. "We need to ensure that the rest of Africa benefits from our experiences," said Dr. Peter Donkor, project leader at Ghana's Kwame Nkruma University.

Courtesy of the MEPI Coordinating Center

MEPI project leaders share their curricula templates,

best practices, research findings and ideas to

maximize efficiency. As the network expands, it will

benefit medical education throughout the region.

Examples of MEPI-driven exchanges between countries abound. During a recent visit, Ugandans observed how the University of Malawi centralizes the administration of its research grants, rather than supporting several grant-specific administrators. Now Uganda's medical schools are setting up similar systems, to curb costs, improve grant tracking and keep a current tally of the university's total grant funding.

Medical institutions in Africa can avoid duplicating specialized curricula if students are able to attend existing courses in other countries. For example, Ghanaian grantees arranged with UKZN for emergency medicine physicians to receive hands-on training in South Africa.

Networking among program participants is producing ties that promise to deepen over time. "Without MEPI, I wouldn't have met many of my colleagues doing great work in other countries," said Dr. David Olufemi Olaleye, project leader at Nigeria's University of Ibadan. "Each of us was working in a different corner of the world. Now we communicate in our common goal of enhancing medical education and planning, and thinking of the next generation of academicians in the region."

Ensuring sustainability

As the ripple effect of MEPI continues, participants are already working to ensure the benefits are sustainable. Encouraging country ownership is key to this effort. In applying for a MEPI award, organizations needed to demonstrate buy-in from national governments - the primary funders of medical education and health services in Africa. This requirement has spurred much more communication between medical schools and ministries, MEPI project leaders reported.

Courtesy of the MEPI Coordinating Center

Amb. Eric Goosby (on right), U.S. Global AIDS

Coordinator, and other MEPI meeting participants

discuss the many changes facilitated by the

program.

"Universities must not act in isolation as if we know it all, but work with relevant government departments so that the plans of those ministries can be brought to bear," Uganda's Sewankambo said. "The degree of collaboration between the Ministry of Health and our training institutions has never been this good. And one is hearing this not only from Uganda but from others under the MEPI initiative."

In Kenya, University of Nairobi grantees invite officials from the ministries of health and education to monthly department head meetings. "Government policymakers approach things with a lot of skepticism, so you really need to convince them that this is important and a desired change," Kenya's Kiarie said. At the same time, he added, the government is not expected to engage in the day-to-day decisions made by what is already a large team of officials from the schools of medicine, dental sciences, pharmacology, nursing and public health.

Since MEPI began in Zambia, medical educators and government officials are communicating in unprecedented ways. For example, the University of Zambia includes a senior health official as an advisor for its MEPI project and consults the ministry before disseminating clinical guidelines to provincial hospitals.

Photo by Richard Lord

for Fogarty/NIH

MEPI project leaders are working

on ways to sustain the enormous

gains they are making in medical

education, including by winning

research funding for their

institutions.

The Zambian government is extending monetary support as well, said Dr. Yakub Mulla, MEPI project leader. "The government has doubled the funding for the training of health professionals," he said. It's also building the new Copperbelt University that will help expand medical education capacity.

When Ghana's MEPI institution launched its project to train emergency medicine physicians and nurses, it included all stakeholders in the planning, including those within various departments in the university, teaching hospital, health ministry, ambulance service and Ghana College of Physicians and Surgeons.

"It was not very straightforward getting everyone onboard," Donkor said. "But now there is great acceptance because everybody really is beginning to see the difference that emergency medicine is making in the care of patients."

Government backing can have dramatic results. Zimbabwe's education ministry recently provided co-funding to the country's MEPI program. Other MEPI sites have similar government pledges in the works.

Project leaders say they hope their successes will inspire additional funding from developed country organizations and philanthropic groups to a topic - medical education - that traditionally has not excited much funder attention.

"The environment is clearly different now from what it has ever been in terms of supporting medical education," Sewankambo said. "I think, based on what funders are now seeing, they are beginning to say, yes, we would like to contribute toward medical and health education."

One organization with a continent-wide reach is the African Medical Schools Association, dormant for several years. MEPI has breathed new life into the organization and given it a focus for action. The association convened its members at the recent MEPI gathering, to facilitate networking especially for its non-MEPI members. The African Development Bank is another organization that could play a role in MEPI's future, to ensure its benefits are widespread and long-lasting.

"MEPI is creating a huge impact. It would help to scale up the program to all countries of the region, also those not part of MEPI," said Dr. Francis Omaswa, who directs the African Center for Global Health and Social Transformation, a network and think tank. "Most of the African economies are growing and there is a lot of hope. MEPI presents Africa with an opportunity to capture this movement of hope."

Page 1 | Page 2

More Information

To view Adobe PDF files,

download current, free accessible plug-ins from Adobe's website.