Fogarty marks 50 years of global health partnerships, considers future directions

May / June 2018 | Volume 17, Number 3

Photo by Andrew Propp for Fogarty/NIH

The best thing about 1968 was the Fogarty International

Center’s creation, said Dr. Richard Horton, editor of

The Lancet, who delivered the keynote address at the

Center’s 50th anniversary symposium.

View more pictures from the symposium in the

50th

Anniversary Symposium Photo Gallery on Flickr.

Photo by Andrew Propp for Fogarty/NIH

Sen. Jack Reed (D-RI) said the Fogarty International Center

remains faithful to the vision of its namesake, Congressman

John E. Fogarty, who was committed to using science to

advance peace and improve health for all people.

By Ann Puderbaugh

A half century of Fogarty’s global health research and training accomplishments were

celebrated May 1, as more than 500 NIH leaders, researchers, advocates and trainees gathered from around the world to mark the Center’s establishment in 1968. Part scientific symposium, part family reunion, the day was devoted to a review of progress in the development of research capacity in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), Fogarty’s role in advancing science to reduce death and disability, and a discussion of new frontiers of global health research ripe for future exploration.

“Never before in the history of global health has global collective action been more important,” said Dr. Richard Horton, editor of The Lancet, in his keynote address. With nationalism and anti-science rhetoric on the rise, evidence-based decision-making is on the decline, he continued. “It feels like we are living through a counter-enlightenment, that some believe that the world is unsafe, unstable and insecure, that the idea of progress is actually a myth, that the promise that we have given society for what science can deliver is actually a lie.”

Horton urged the audience to extend efforts to improve global health in a number of key areas, including reducing child mortality, accelerating progress in reproductive health, improving understanding of the prevention and treatment of noncommunicable diseases, and finding ways to lessen health-related suffering, which he said impacts about 61 million people worldwide. The research community should also carefully consider the evolving health threats posed by climate change and environmental hazards, he suggested. Another priority must be continuing to train health professionals in LMICs, where many populations are underserved, so that the ultimate goal of achieving universal health coverage can be reached.

Honoring the Center’s namesake

The Center remains faithful to the vision of its namesake, according to Sen. Jack Reed (D-RI), who recalled that Congressman John E. Fogarty was known for his effectiveness, decency and kindness. Not only a champion for the NIH, Fogarty also believed the U.S. had an obligation to improve health around the world. He argued for a “Health for Peace Center” that would embody Americans’ commitment to use science for the good of mankind. “That vision permeates this Center,” said Reed.

He pledged continued support for the Fogarty International Center and its work, and acknowledged the effective advocacy conducted on its behalf by Congressman Fogarty’s daughter, Mary Fogarty McAndrew, and her husband Tom McAndrew, who attended the celebration with their children and grandchildren.

Advancing infectious disease research and ending AIDS

In the first panel discussion, devoted to HIV/AIDS and the infectious disease agenda, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Director Dr. Anthony S. Fauci noted the NIH investment in research that led to antiretroviral therapy (ART) literally transformed the lives of those living with HIV. ART and other advances in prevention and treatment give him optimism. “We really have no more excuses. We do have the tools with treatment and prevention to actually end the AIDS pandemic as we know it.”

Photo by Andrew Propp for Fogarty/NIH

The first panel discussion concerned HIV/AIDS and

infectious disease research. From left, Drs. Sten Vermund,

Linda-Gail Bekker, Jean “Bill” Pape, Quarraisha Abdool Karim

and Anthony S. Fauci.

Photo by Ann Puderbaugh/Fogarty/NIH

National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID)

Director Dr. Anthony S. Fauci assisted Fogarty Director

Dr. Roger I. Glass with his emerald green bow tie, worn in

honor of the Center’s namesake, Congressman. John E.

Fogarty, who used bow tie-shaped billboards in his

political campaigns.

Young women pose a critical challenge to ending the epidemic in Africa, with 5,000 new infections occurring each day, according to Fogarty grantee Dr. Quarraisha Abdool Karim. Papers published with contributions by Fogarty trainees give glimpses of the physical and behavioral reasons young women hold the key to reducing transmission, she said. As associate scientific director of the Centre for the AIDS Programme of Research in South Africa, known as CAPRISA, she suggested gender power disparities must be addressed and that young people should be part of the solution.

Dr. Linda-Gail Bekker, professor at the University of Cape Town, told her personal story of progressing from an M.D. looking to advance in South Africa - where only 4 percent of graduate students finished their Ph.D.s at the time - to traveling to Rockefeller University in New York with Fogarty support. “That opened up a whole world of exciting science and discovery,” she said. Now deputy director of the Desmond Tutu HIV Centre, she is also president of the International AIDS Society.

In Haiti, another former Fogarty trainee established and leads the Haitian Group for the Study of Kaposi’s Sarcoma and Opportunistic Infections, which is known by its French acronym, GHESKIO. Longtime grantee Dr. Jean “Bill” Pape said he has trained about 500 scientists with Fogarty support, many in infectious disease research. His country is also seeing climbing rates of HIV infection in young women. He said an implementation science focus should be used to study interventions in key populations - particularly adolescents and young adults - and a community approach should be considered, including actions to reduce poverty.

Dr. Sten Vermund, longtime Fogarty grantee and Dean of Yale University’s School of Public Health, has spent decades overseeing research training programs in LMICs. Vermund highlighted a cancer prevention project in Zambia, begun with Fogarty trainees, that has grown into a cervical and breast cancer prevention Initiative program that has screened about 300,000 women and is now a training site for the entire world. “It’s remarkable how a small Fogarty investment, a small PEPFAR investment, can then blossom into a major program.”

Photos by Andrew Propp for Fogarty/NIH

The growing global threat of chronic diseases was

considered by former Fogarty fellow Dr. Satish Gopal, NCI

Deputy Director Dr. Douglas R. Lowy and President of the

South African Medical Research Council Dr. Glenda Gray.

The discussion of noncommunicable diseases included

presentations on cancer, cardiovascular conditions and

sickle cell disease.

Leveraging existing research and training platforms for NCDs

Another panel further explored the growing burden of chronic, noncommunicable diseases. In addition to developing a number of its own funding programs to support NCD research and training, Fogarty also helped establish the Global Alliance for Chronic Diseases (GACD), said its chair, Dr. Glenda Gray, who’s also President and CEO of the South African Medical Research Council. Since 2011, the 14 research agencies partnering through GACD have jointly funded $178 million of research on hypertension, diabetes, lung diseases and mental health.

Global research collaborations are key for progress, National Cancer Institute (NCI) Deputy Director Dr. Douglas R. Lowy said. For instance, studies in Costa Rica provided data that suggests a single dose of the human papilloma virus vaccine may offer protection against cervical cancer, which could be significant for low-resource settings. Two former Fogarty fellows who are now co-PIs on an NCI grant said NIH support has changed the landscape of cancer care and research in Malawi. Dr. Satish Gopal, Malawi’s only oncologist, said Fogarty investments sparked what has now grown into a substantial research site that has produced numerous publications and alumni, resulting in additional NIH and other funding. Gopal’s Malawian colleague, Dr. Sam Phiri, told how he progressed from Fogarty trainee to NCI grantee.

NIH programs should empower country-driven contextual solutions to bend the curve and help eliminate health inequities, according to National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) Director Dr. Gary Gibbons. He detailed his Institute’s global efforts to reduce household air pollution exposure, study low-cost hypertension interventions and translate advances in sickle cell disease to LMICs. NHLBI grantee Dr. Julie Makani, of Tanzania’s Muhimbili University, said she hopes genomics studies in Africa may lead to advances that can benefit sufferers everywhere.

There was no pathway for cardiologists interested in global health when he graduated from medical school, said Dr. Gerald Bloomfield. “Fogarty came into my sphere of understanding at a critical point in my career,” he said. His experience as a Fogarty Fellow studying the causes of heart failure in Kenya helped him transition into a principal investigator with his own research funding. He now mentors Kenyan trainees and has helped build a vibrant and active research environment in the country.

Photo by Andrew Propp for Fogarty/NIH

The research agenda for global brain disorders was

discussed by a panel moderated by Fogarty Deputy

Director Dr. Peter Kilmarx (far right), with speakers including

Fogarty advisory board member Dr. Gretchen Birbeck, of the

University of Rochester (left), and National Institute of

Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) Director

Dr. Walter Koroshetz (center).

Advancing global mental health, brain disorders research

Brain disorders also cause an enormous disease burden in the developing world. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Director Dr. Walter Koroshetz and grantee Dr. Gretchen Birbeck jointly presented on stigma and epilepsy. Koroshetz explained the shortage of neurological expertise in many LMICs means Western solutions are often not possible to implement. Birbeck says her studies to find cost-effective interventions for epilepsy in Zambia have shown working with peer groups and schools can be helpful. Each Fogarty grant is like a pebble in a pond, she said. “What we don’t really appreciate unless we step back … is all the rippling effects that occur as the result of a small investment by Fogarty.”

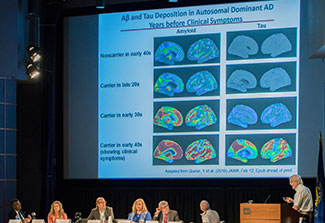

Another team, made up of National Institute on Aging Director Dr. Richard Hodes and grantee Dr. Kenneth Kosik, described an extended family of Colombians with a genetic mutation that brings early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Kosik said he used Fogarty funds to build local scientific capacity to study the population, which has made it possible for the site to be included in an ongoing drug trial to see if Alzheimer’s can be stopped at its earliest point. He also said the team has established a brain bank there, an untapped resource that is waiting to be explored. Hodes says the courageous families’ commitment to the research is “extraordinary.”

Photos by Andrew Propp for Fogarty/NIH

Fogarty’s Amit Mistry spoke to Dr. Shelli Avenevoli, deputy

director of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH),

about the Center’s new initiative on conducting research

during humanitarian crises.

National Institute on Aging (NIA) Director Dr. Richard Hodes

described the unique research opportunities in Colombia,

where a clinical trial is testing a drug to see if it can prevent

Alzheimer’s disease from developing.

The National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) has also had “fruitful partnerships” with Fogarty, said its Deputy Director Dr. Shelli Avenevoli, and has future plans to develop LMIC data infrastructure and analytic capacity, advance implementation science, and conduct research in the humanitarian context. NIMH grantee Dr. Vishwajit Nimgaonkar said his funding for genomic studies of schizophrenia in India and Egypt has allowed him to develop sufficient capacity that the local scientists now work on an equal basis with their U.S. partners. Nimgaonkar says he has trained 70 psychiatrists and psychologists in research techniques, established genomics labs, developed ethics guidelines for mental health research, and contributed samples to genetic banks.

Trainees become the trainers

The final session focused on the multigenerational impact of Fogarty’s research training programs. As a young girl growing up in Peru, Dr. Patty Garcia said she dreamed of being a super hero who could improve the lives of her country’s people. After medical school, she received Fogarty support for advanced studies at the University of Washington, where she earned her master’s in public health and Ph.D.

Since returning home, she has built a cadre of well-trained scientists - including co-presenter Dr. Magaly Blas - who have successfully competed for numerous research grants from NIH and other funders. Fogarty programs helped advance understanding of infectious diseases in Peru, develop expertise in informatics, incorporate electronic medical records into the national health system, and expand research into the Amazon region and other underserved areas. All the while Garcia has progressed in her career, serving as dean, director of Peru’s NIH and recently as health minister.

“Every step you take in life shapes who you are,” she said. “And the steps I’ve walked with the help of Fogarty were instrumental in helping me to achieve a great deal, including being appointed health minister.”

In South Africa, ongoing Fogarty support since 1992 has helped train more than 600 scientists. “For me, the most important thing is that almost every study on HIV going on in South Africa today involves a Fogarty trainee in some way or another,” said Dr. Slim Abdool Karim. He introduced his protégé, Dr. Vivek Naranbhai, who said his experience as a Fogarty fellow was life-changing.

Photo by Andrew Propp for Fogarty/NIH

The symposium’s final panel explored multigenerational

models of long-term research capacity building. From left,

Dr. Vivek Naranbhai and his mentor, Dr. Salim Abdool Karim,

Director of CAPRISA in South Africa, and Fogarty Director

Dr. Roger I. Glass, who moderated the session.

Naranbhai, now a resident at Harvard University, said he entered the program feeling he was an inconsequential physician, but during orientation at NIH quickly realized he had something to offer. “It introduced me to a community of like-minded people - to suddenly have access to this great global village is extraordinary.”

Uganda has also benefitted from Fogarty research training support, according to Dr. Nelson Sewankambo, of Makerere University. In particular, he highlighted the Medical Education Partnership Initiative (MEPI), which was administered by Fogarty with funding from NIH and the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief. “Moving forward, these achievements need to be sustained and scaled-up,” he said, and African resources should be mobilized.

His trainee, Dr. Mark Kaddamukasa, said NIH and Fogarty played a critical role in his career development. Now with his own NIH grant, he has in turn mentored more than a dozen students. He says this concept is reflected in an African saying, “When you walk in the path of your father, you learn to walk like him.”

Photos by Andrew Propp for Fogarty/NIH

NIH Director Dr. Francis S. Collins (center) reminisced with

Fogarty Director Dr. Roger I. Glass (left) and Dr. Warren

Johnson, who is the founding director of Weill Cornell

Medicine’s Center for Global Health.

Mary Fogarty McAndrew, Congressman John E. Fogarty’s

daughter, toasted the Fogarty International Center’s

accomplishments and commitment to her father’s dream

of fostering scientific partnerships to improve global health

at a reception hosted by the Foundation for the NIH.

Fogarty programs that develop these local research leaders are the key to the future, said NIH Director Dr. Francis S. Collins. “We want to increasingly empower investigators in-country to be able to be in charge of their own efforts, to figure out what the most important research questions are in their environment and then to help them build support for that within their own countries,” he said. “Even with its modest budget, Fogarty can be an incredible catalyst.”

The other Institutes, Centers and Offices at NIH have been Fogarty’s greatest partners in building these international collaborations, with almost 90 percent of Fogarty grants receiving co-funding, noted Fogarty Director Dr. Roger I. Glass. “By forming and supporting these scientific partnerships, the Center has tried to expand the envelope of research,” he said. “The principal value of Fogarty is investing in people and their careers.”

- Watch this session:

Welcome remarks

by Dr. Roger I. Glass, Director, Fogarty International Center

More Information

To view Adobe PDF files,

download current, free accessible plug-ins from Adobe's website.