Leprosy's tragic past recalled in NIH exhibit

May / June 2012 | Volume 11, Issue 3

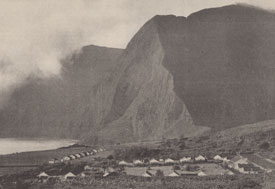

Photo courtesy of National Park Service Archives

Young Hawaiian boys with leprosy were banished

to the remote island settlement of Kalaupapa,

away from their families and friends.

On a beautiful location in the Hawaiian archipelago, one settlement has a ghastly past: Kalaupapa's residents were stranded there because they had Hansen's disease, also known as leprosy. Their chilling story is relayed in the NIH's National Library of Medicine multimedia exhibition, "Native Voices: Native Peoples' Concepts of Health and Illness."

The feared and then-untreatable disease arrived in Hawaii with merchant sailors in the 1840s. "The disease became epidemic. There arose a fear that perhaps Hawaii would become a bastion of leprosy," according to Dr. S. Kalani Brady, a professor and physician in Hawaii who treats the islands' remaining Hansen's disease patients. This fear spurred the authorities to take harsh action.

Starting in 1866, they processed as criminals anyone suspected of having a telltale skin blemish. First, the person was arrested and examined, naked, by a circle of experts. Those convicted were boated to the Kalaupapa settlement on Molokai Island. They could not escape past the 3,000-foot-high cliffs separating them from the rest of the island or the shark-infested ocean and were left to spend the rest of their curtailed lives void of medical support, rule of law or any further contact with family.

Firsthand accounts preserved by the Kalaupapa National Historical Park reveal how people felt about being sent to this remote place, and of the conditions they faced.

Photo courtesy of Carl W. Bell,

Baylor University Electronic Library

Beginning in 1866, more than 8,000 Hawaiians

with leprosy were confined on the island of

Molokai, where they could not escape due to

the high cliffs on one side and shark-infested

ocean on the other.

"One of the worst things about this illness is what was done to me as a young boy," recalled one resident. "First, I was sent away from my family. That was hard. I was so sad to go to Kalaupapa. They told me right out that I would die here; that I would never see my family again. I heard them say this phrase, something I will never forget. 'This is your last place. This is where you are going to stay, and die.' That's what they told me. I was a thirteen-year-old kid."

The residents had some relief, however, when in 1873 missionaries began to move to the island and offer care. U.S. health authorities launched a concerted, scientific attack on leprosy, from the early 1900s, Brady noted, but growing the bacteria was difficult until researchers identified armadillos as suitable hosts. In the 1940s, sulfone drugs were found to be effective against the disease, but some patients remained confined in Kalaupapa until 1969. By then, more than 8,000 patients had been banished there. The site has been preserved as Kalaupapa National Historical Park and 20 Hansen's disease patients voluntarily live in the area.

The "Native Voices" exhibition content is available online and at the NLM's museum on the NIH campus through autumn 2013. The Kalaupapa story illustrates the devastating impact of external contact on Native Hawaiian health, the exhibit notes, but also illustrates how advances in medical knowledge can overcome ignorance.

Leprosy today

Leprosy, also known as Hansen's disease, has been successfully treated since the middle of the last century, but is still not eliminated. Caused by Mycobacterium leprae, pockets persist in some African countries, Brazil, India and Nepal. The WHO recorded nearly 230,000 new diagnoses in 2010.

It is the unlucky few who develop the disease. About 95 percent of people infected with M. leprae do not develop leprosy because their immune system fights off the infection. The bacteria enter the body via the skin or more often the respiratory tract, spreading from human, armadillo or some primate vectors. The incubation before symptoms show can be as short as a few weeks or as long as 20 years.

More Information

To view Adobe PDF files,

download current, free accessible plug-ins from Adobe's website.