Discovering the character of sepsis in sub-Saharan Africa

May / June 2022 | Volume 21 Number 3

Nearly 85% of an estimated 30 million annual cases of sepsis occur in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Sepsis—a life-threatening condition which develops when a patient’s immune system responds in an extreme way to an infection—can lead to tissue damage, organ failure, even death. In developed countries, sepsis usually results from severe bacterial infections in older people with multiple medical problems like diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer. No single effective therapy for sepsis exists, yet decades of studies in the U.S., Europe and Asia have led to unified treatment guidelines.

Not so in Africa.

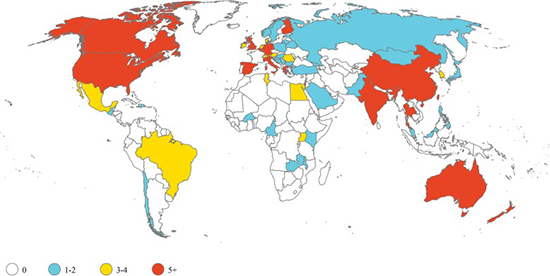

Illustration courtesy of Kristina E. Rudd, et al.Sepsis trials are predominantly conducted in high-income countries. Yet nearly 85% of annual cases occur in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).

Illustration courtesy of Kristina E. Rudd, et al.Sepsis trials are predominantly conducted in high-income countries. Yet nearly 85% of annual cases occur in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).

“In sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), we have a poor understanding of the pathophysiology of sepsis since, essentially, every conceptual model reflects host and pathogen features relevant to the Global North,” said Dr. Matthew Cummings. To start, sepsis is more common in SSA because there’s no shortage of pathogen diversity. “Bacteria, mycobacteria, parasites (most commonly malaria), viruses including chikungunya, yellow fever, Ebola, and COVID-19 —a wide variety of pathogens cause sepsis in Africa,” said Cummings. Antimicrobial resistance adds one more challenge. “If you don't have a precise understanding of the pathophysiology, how can you develop targeted, locally relevant treatment strategies?” This question is at the heart of Cummings’

NIAID-funded project, which aims to classify sepsis patients in SSA into subgroups so that diagnostic and treatment strategies can be precisely tailored.

“Three recent clinical trials in SSA deployed sepsis management strategies derived from high income countries… and all three trials actually caused harm,” said the assistant professor of medicine at Columbia University. “We really need to take a pause and figure out what exactly, at a fundamental biological level, is sepsis in Africa?”

Given higher case numbers, SSA shoulders the greatest burden of sepsis-related deaths (about 40% of the global total). “A lot of that is driven by the ongoing HIV epidemic, which complicates treatment in Africa," Cummings said. Sepsis patients are usually younger and have HIV or another co-infection not frequently seen in high-income countries. "Underneath all of this," added Cummings, "are profoundly under-resourced health systems.”

And this is where antimicrobial resistance gains a foothold. “You don't have consistent supplies of oxygen, let alone electricity in many frontline SSA hospitals,” said Cummings, explaining that considerable resources are needed to run conventional laboratory tests to correctly identify pathogens and which antibiotic agents to use for treatment. Add to that the antibiotics that treat resistant bacteria are newer and more expensive, he noted. Recent data from Malawi indicates 83% of septic patients receive ceftriaxone, a frontline antiimicrobial recommended by the World Health Organization. But it will only be effective in about a quarter of all patients, in part because many pathogens have developed resistance to it.

How, then, can Africa reduce its burden of sepsis? First, increase recognition of the syndrome at the community and hospital level to improve emergency care, said Cummings. Second, untangle heterogenous biological features of the syndrome to identify, test and deploy precision treatments. “

We recently published a paper in

Critical Care, showing for the first time that biological sepsis subtypes exist in SSA (in our case Uganda) that have distinct biological profiles that are associated with unique host-pathogen features and outcomes.” Finally, address the role played by HIV-associated tuberculosis in SSA.

“When you're talking about sepsis in Africa, you’re really talking about HIV and if you’re talking about HIV, you’re really talking about severe and disseminated TB.” Cummings’ work shows that patients with HIV, particularly those with HIV and TB, have more extensive organ dysfunction, worse survival, and among those who survive, worse functional outcomes.

Cummings’ ongoing research seeks to validate the biological subtypes he’s identified in a broader, geographically diverse group of patients enrolled at two hospitals in Uganda. “Our major study site became a national COVID-19 referral hospital in Uganda, so we ended up enrolling those patients in our study. We know very little about the pathophysiology of COVID in Africa and how HIV relates to that so that’s an additional component of the work.”

More Information

Updated June 15, 2022

To view Adobe PDF files,

download current, free accessible plug-ins from Adobe's website.